Topiramate and Kidney Stones: Essential Facts and Prevention Tips

Quick Takeaways

- Topiramate can raise the risk of kidney stones by altering urinary chemistry.

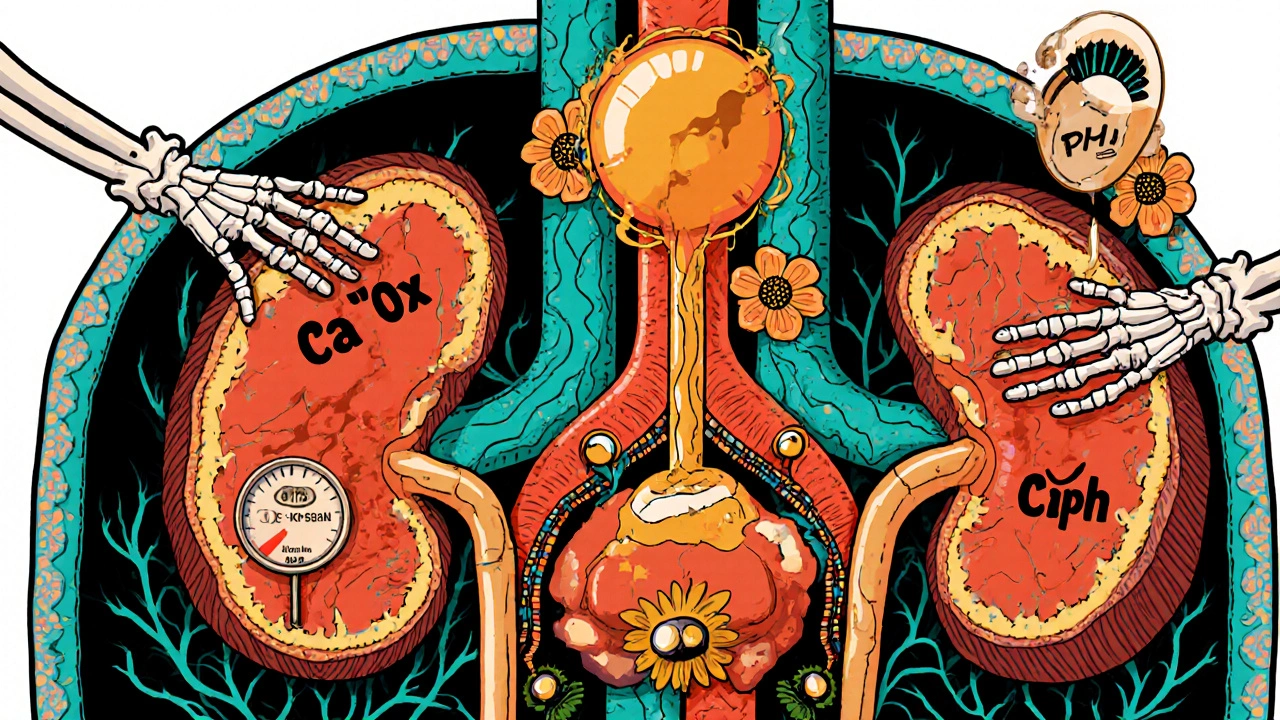

- Most stones linked to the drug are calcium‑oxalate or calcium‑phosphate.

- Staying well‑hydrated and monitoring urine pH are the simplest preventive steps.

- Doctors should check serum bicarbonate and renal function before and during therapy.

- If a stone forms, treatment options range from extra fluid intake to minimally invasive procedures.

When you hear about Topiramate is an oral medication used for epilepsy and migraine prevention, the conversation usually focuses on its effectiveness in controlling seizures or reducing headache frequency. What’s less talked about is that topiramate can tip the balance of minerals in your urine, making stone formation more likely.

How Topiramate Works

Topiramate belongs to a class of drugs called sulfamate‑substituted monosaccharides. It stabilizes neuronal membranes by enhancing gamma‑aminobutyric acid (GABA) activity and blocking sodium channels. Two side effects are especially relevant to kidney health:

- Carbonic anhydrase inhibition - the drug mildly blocks this enzyme, causing a modest metabolic acidosis.

- Increased urinary calcium excretion - the shift in acid‑base balance can raise calcium levels in the urine.

Both mechanisms create a favorable environment for crystal formation.

What Are Kidney Stones?

Kidney stones hard mineral deposits that form inside the kidneys are commonly called nephrolithiasis. They can be made of several substances, but the two most frequent types associated with topiramate are:

- Calcium‑oxalate stones - form when calcium binds with oxalate in acidic urine.

- Calcium‑phosphate stones - tend to appear in alkaline urine, a condition topiramate can provoke through chronic acidosis.

Less common varieties include uric acid, cystine, and struvite stones, each with its own risk profile.

Why Topiramate Increases Stone Risk

The link is mostly biochemical:

- Metabolic acidosis: Inhibiting carbonic anhydrase reduces bicarbonate reabsorption, lowering serum bicarbonate levels. The kidneys compensate by excreting more acid, which can raise urinary calcium.

- Urinary pH shift: A drop in systemic pH often leads to a higher urinary pH, especially when the body attempts to buffer the acid load. Alkaline urine favors calcium‑phosphate crystal growth.

- Dehydration risk: Some patients experience mild diuresis or reduced thirst as a side effect, cutting down fluid intake and concentrating urine.

Combined, these changes mean that the supersaturation index for calcium‑based salts climbs, and the chance of a stone forming rises.

Who Is Most at Risk?

Not everyone on topiramate will develop stones. The following groups need extra attention:

- Individuals with a personal or family history of nephrolithiasis.

- Patients who already have low urine volume (e.g., those on a low‑fluid diet).

- People with metabolic conditions such as hypercalciuria or hypocitraturia.

- Women of child‑bearing age-pregnancy alters calcium handling, and the drug is often prescribed off‑label for migraine.

Signs and Symptoms to Watch For

Kidney stones can be silent, but classic clues include:

- Sharp flank pain that may radiate to the groin.

- Hematuria (blood in the urine) giving a pink or cola‑colored flush.

- Frequent urge to urinate, sometimes accompanied by nausea.

- Fever or chills if a stone leads to infection.

If any of these appear after starting topiramate, prompt medical evaluation is advisable.

Prevention Strategies for Patients

Prevention is a blend of lifestyle tweaks and occasional lab checks:

- Hydration: Aim for at least 2.5-3 L of urine output per day. A practical rule is to drink enough that your urine stays pale yellow.

- Dietary calcium: Don’t cut calcium dramatically; a steady intake (1,000‑1,200 mg/day) helps bind oxalate in the gut.

- Oxalate moderation: Limit high‑oxalate foods like spinach, rhubarb, and nuts if you’re prone to calcium‑oxalate stones.

- Limit sodium and animal protein: Both increase calcium excretion.

- Monitor urinary pH: Home pH strips can guide adjustments; keep pH around 6.0‑6.5 for most people.

- Regular lab work: Serum bicarbonate, creatinine, and urinary calcium checks every 3‑6 months are recommended, especially during the first year of therapy.

What to Do If a Stone Forms

Management depends on size and location:

- Stones < 4 mm often pass spontaneously with increased fluid intake and a short course of an alpha‑blocker such as tamsulosin.

- Stones 5‑10 mm may require extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) - a non‑invasive method that breaks the stone into passable fragments.

- Larger or obstructive stones often need ureteroscopy with laser lithotripsy or percutaneous nephrolithotomy.

After removal, the focus returns to preventing recurrence by adjusting the topiramate dose, switching to an alternative antiepileptic if feasible, and reinforcing the hydration plan.

Clinical Tips for Prescribers

Doctors can lower stone risk without sacrificing seizure or migraine control:

- Screen baseline labs: serum bicarbonate, creatinine, calcium, and a 24‑hour urine calcium test.

- Consider a lower starting dose and titrate slowly; the stone risk correlates with dose intensity.

- Educate patients about early symptoms and the importance of drinking enough water.

- If a patient develops stones, evaluate whether the dose can be reduced or if switching to levetiracetam, gabapentin, or lamotrigine (which have lower stone profiles) is appropriate.

- Document stone‑related adverse events in the patient’s record; this helps with future drug‑choice decisions.

Comparison of Antiepileptic Drugs (AEDs) and Stone Risk

| Drug | Primary Indications | Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibition | Reported Stone Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Topiramate | Epilepsy, migraine prophylaxis | Yes (moderate) | Increased (≈3‑5% of users) |

| Acetazolamide | Glaucoma, altitude sickness | Strong | High (≥10%) |

| Levetiracetam | Epilepsy | No | Low (≈0.5%) |

| Lamotrigine | Epilepsy, bipolar disorder | No | Very low |

Choosing an AED with a lower stone‑formation profile can be a practical way to mitigate risk, especially for patients with a prior history of nephrolithiasis.

Bottom Line

Topiramate is a highly effective drug for seizure control and migraine prevention, but its impact on urinary chemistry means a higher chance of kidney stones. Staying hydrated, monitoring labs, and being alert to early symptoms can keep the problem at bay. When stones do appear, they are usually manageable with standard urological treatments, and dose adjustments often prevent recurrence.

Does every patient on topiramate develop kidney stones?

No. Only a small percentage-around 3‑5%-experience stones, and the risk rises with higher doses and pre‑existing stone history.

Can I lower my stone risk by drinking more water?

Absolutely. Aim for urine output of at least 2.5 L daily; dilute urine reduces crystal formation dramatically.

Should I stop topiramate if I develop a stone?

Not necessarily. Your doctor may lower the dose, switch to another medication, or add prescription for alkalinizing agents while you undergo urological treatment.

Are certain foods more likely to cause stones while on topiramate?

High‑oxalate foods (spinach, beetroot, nuts) can increase calcium‑oxalate stone risk. Pair them with calcium‑rich foods to bind oxalate in the gut.

How often should I get lab tests while taking topiramate?

Baseline labs before starting, then every 3‑6 months for the first year, and annually thereafter, focusing on serum bicarbonate, creatinine, and urinary calcium.

Hydration is the only magic you need.

When you read about a drug that messes with your kidneys you start to wonder why no one mentioned the shadowy push from big pharma to keep us hooked on endless prescriptions I mean the very fact that a medication can turn your urine into a crystal garden feels like a silent conspiracy hidden in plain sight it’s almost as if they want us drowning in doctor visits while we chase the next pill the truth is buried in the fine print and the lab reports that look like ancient hieroglyphs only a select few seem to decode the warning signs I suspect there’s a coordinated effort to downplay side effects for profit I’ve seen the same pattern with other meds where the risks are brushed off with a smile and a brochure the scientific community whispers about metabolic acidosis and calcium excretion but the headlines scream miracle seizure control I’m not saying the drug is evil but the lack of transparency feels like an ethical breach you deserve to know that your urine chemistry is being hijacked by a tablet you swallow daily and that your doctor might not even monitor the subtle shift until a stone blocks your life I think it’s time we demand mandatory quarterly urine pH checks when on such drugs and push back against the complacent acceptance of side effects as inevitable

Yo, topiramate’s got that sweet spot for seizures but it also sneaks in a calcium‑oxalate party in your kidneys – talk about an unwanted houseguest. Drink water like you’re training for a marathon, toss in some citrus, and keep those crystals at bay. If you’re into flavor, splash some lemon or lime; the acid helps dissolve tiny stones before they grow. And hey, don’t forget to watch the sodium – salty snacks are basically a stone‑making factory. Bottom line: you can stay seizure‑free without ending up a human geode.

Can you even imagine the drama when a kidney stone decides to make a cameo during a migraine episode? It’s like the universe saying, "Not today, buddy!"

Staying hydrated and checking urine pH are simple steps. If you keep your urine pale yellow you’re already on the right track.

Make a habit of a daily water log. It’s an easy way to see if you’re meeting the 2.5‑3 L goal.

Honestly, if you’re on topiramate and you skip the hydration game you’re basically inviting trouble. It’s not just a suggestion, it’s a responsibility to your own body.

Philosophically speaking, a stone is just a reminder that even our bodies seek balance; when we tilt the scale with medication, nature finds a way to restore it 😊.

Look, mates, the real patriotism is taking care of your own health – don’t let a foreign‑made pill turn your kidneys into a battlefield. Stay hydrated, check your labs, and you’ll keep fighting the good fight.

Topiramate modulates GABAergic signaling, impacts H+ secretion – leads to supersaturation of calcium salts; watch renal clearance metrics.

From a practical standpoint, I recommend setting a reminder to drink a glass of water every hour. Pair that with a quarterly check of serum bicarbonate and urinary calcium, and you’ll catch any drift early.

Hey everyone, just wanted to say that it’s totally okay to feel overwhelmed by all this medical info! 🌟 Remember to take one step at a time – drink that water, schedule that lab, and celebrate each small win. You’ve got this, and we’re all here cheering you on! 🎉

Keeping an eye on your diet is key – cut back on high‑oxalate foods while still getting enough calcium. Also, track urine color; if it’s dark, you need more fluids.

Let’s keep the conversation upbeat and share our hydration hacks!